There was so much work back then that you could quit one job in the morning

and have another lined up the same day and go to work.

One can’t speak of the history of Florence without including the logging industry’s significant role in the heritage of the Siuslaw Valley. Once a primary contributor to the economy of Florence, logging and those who made it their lifestyle is a legacy to be looked upon with acknowledgement and respect. While those bygone days may be considered a simpler life, it was also a time that embraced the true pioneer spirit.

A Logger’s Life

A Logger’s Life

Darrel W. Bunch was born in 1949, in Dr. Dunn’s office, above the town’s pharmacy. Growing up back then, Florence had a population of about 1000 residents. His family roots run deep. His mother (Agnes Miles) was a pioneer family member from Fiddle Creek. Darrel’s father (James William Bunch, Jr.), grandfather (James William Bunch, Sr.) and great-uncle (Ben Bunch) all homesteaded on Big Creek.

Raised in Florence, Darrel attended Siuslaw High School. In 1967 at 18 years old, he began working as a tree faller, having learned the skill from his father. He worked at LaDuke Lumber where James Jr. was a bullbuck (supervisor or boss of timber fallers and buckers) for a year until its closure. He continued working as a contract tree faller with his father, who had previously logged for Crown Zellerbach, Mount Canary, and a number of other logging outfits. For their livelihood, they contracted for timber cutting jobs throughout the years with various companies. Darrel acknowledged it was common practice for companies to acquire areas through timber sales, and contract out the tree cutting jobs. As such, most of his logging career was working on a contract basis with Davidson Industries (“Davidson”), Champion and U.S. Plywood in Mapleton and others.

Working as a Contract Cutter

As an example of how contract workers operated, payment for timber cutting was based on the thousand board feet. Darrel explained that back in the day, the rate was $10 per thousand. If 20,000 board feet were cut that day, payment would be $200. When bidding for a job, Darrel ‘walked the site’, and with his experience, would determine how much timber (board feet) he could cut in a day. If his bid was accepted, he would sign a contract for the tree falling job. He cautioned those numbers reflect a time when jobs were based on wood scale. Years later, the method was changed to truck scale, where a truck would come into the mill and its logs would be “scaled” to determine the rate per thousand. Trucks would typically have 5,000 board feet, so if it were $10 per thousand board feet, then a truck would be paid $50 per truck load. Based on that rate, 4 truck loads would amount to $200.

To compare those numbers with more current rates, Darrel mentioned a job he bid 1 ½ years ago for Coast Road Construction during the winter at Alsea. His accepted bid was $50 per thousand board feet.

Current Practices and New Regulations

Darrel stated the current practice is only ‘smaller wood’ (i.e. smaller trees) are being cut for clear cutting jobs. As such, the method now used is to bid by the tonnage. According to him, the change to tonnage was a result of new federal legislation which prohibits logging in the Siuslaw forest range. The mandate was an environmental effort to ‘save’ the larger, old-growth trees. He acknowledges and attributes more tree growth exists today than in prior years due to reforestation (re-planting) efforts. Despite the increased growth however, trees over a certain diameter on federal land, are still prohibited from being harvested. Only “thinning”, or harvesting smaller diameter trees are allowed. (The ruling does not apply to privately owned land.)

With regulations prohibiting the harvesting of large diameter logs, the mills were forced to adapt their equipment in order to process smaller logs. Consequently, few mills today (Swanson Brothers in Noti and another mill on HWY 99) are the only operations capable of handling the larger diameter logs.

Another federal law resulting in a significant impact on the local logging industry was directed at the use of log rafts. At one time, felled logs were stored in the river then wrapped together as rafts and floated to the mill. Crews were required to ‘clean-out’ creeks of debris caused by logging. New regulations halted the log raft practice, citing environmental issues – log debris, and potential harmful effects on the fish population. Conflicting opinions were voiced, citing the rafts were actually beneficial, as fish utilized the rafts as a refuge to hide under, or rest before swimming upriver to spawn. Log rafts however, remained prohibited.

Weather Conditions, Dangerous Work

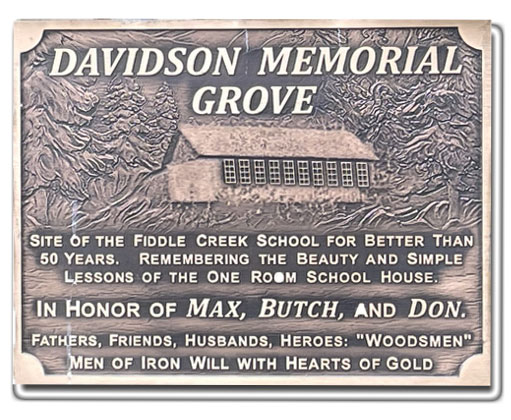

In a 1950 logging accident, Darrel’s father suffered a broken back. He managed to drag himself out of the woods with poles to seek medical help and was driven to Mapleton. After recovering, he fished commercially for a few years, but ultimately returned to logging in the woods. Other than being snowed out, or during exceptionally stormy winter days, local logging is done year round. As much as he enjoyed his career as a timber faller, Darrel is quick to admit having had “a lot of close calls”. While the idea of working in the woods for a livelihood can seem adventurous, it fails to underscore the realities of the danger. USA Today once referred to logging as the most dangerous job in America as of 2018. Darrel described an incident that occurred in 1999. He had been working on a jobsite for Davidson Industries with Phil Davidson, Charles “Max” Lee and Robert George “Butch” Shanklin in the Siltcoos Lake area. A tremendous rainstorm with heavy winds ensued. Due to the weather, Darrel and Phil decided to quit for the day and left the site for home. By evening, Max and Butch had failed to return home. Darrell returned to the site and learned the unrelenting rainstorm had caused a devastating mudslide. Max and Butch had remained at the site and tragically, were killed in the slide. A monument in Fiddle Creek was established in their honor.

Mill Closures

Following the 1999 mudslide incident, Darrel worked for Davidson Industries for 5 years prior to its closure. According to Darrel, the timing of the mill’s closure was not entirely a surprise. The economic recession, environmental concerns, Endangered Species Act and new logging regulations were major challenges. Earlier, the Murphy Mill had shutdown primarily due to the reduced availability of timber.

For years the mills relied on government timber sales as their source for logging. When the Siuslaw National Forest became protected from logging, the mills no longer had a resource for timber. When Champion shut down, Davidson bought their upper mill and converted it into a veneer plant. It operated for a number of years before closing. Their chip mill also closed. The lumber mill continued to operate, but in time, it also shut down. Much of Davidson’s timber grounds were sold to an investment company. Through timber sales, some logging on it still continues with local loggers. Roseburg Forest Products, among the largest timber land owners in our vicinity, also purchased much of what was once owned by Davidson. Darrel pointed out that unlike Davidson, Roseburg is a land-based operation, and therefore not reliant on the river for its operation.

Darrel witnessed the departure of many loggers who were forced to relocate from the Florence area due to the mill closures. Looking back, he recalls when lumber production was at its height, the lot near Dunes Café would fill each morning with cars belonging to loggers. It was a designated location where the crummies (crew vehicles) would pick up workers and transport them to a work site. “There was so much work back then that you could quit one job in the morning and have another lined up the same day and go to work.”

For about 6 years, Darrel worked for Columbia Helicopters in various states (CA, WA, Idaho). Inaccessible by vehicles, logs were flown out of the timber site. A ‘unit’ or area of 100 acres, or so would be cut and the timber logged with a helicopter. He estimates that size of an area would usually require about 15 to 20 tree fallers. The bullbuck determined where the cutting would start, and a project that size could be completed in about 3 to 4 weeks.

Logging as a Way of Life

When asked, Darrel is quick to acknowledge he never desired to do any other kind of work. Although he confesses to occasional second thoughts of not having another occupation to fall back on, he nonetheless admits the woods was where he always wanted to be. Looking back, he contends he enjoyed his 53 years cutting timber and retired just last year (2022).

It was a pleasure to meet with Darrel Bunch and learn about the logging industry through his eyes. It was easy to see his experiences as a tree faller was a fulfilling one.

Story by Deb Lobey, October, 2023

Interview Transcription by Suzanne Korosec

Audio and transcript may be viewed at museum’s Kyle Research Library